There’s a mythical and distant quality to the actual man whose name has become a company brand and iconic representation of corporate consumerism in today’s society that has led the world to disavow any real sense of personality behind a faceless corporation. After all – Walt Disney was many things: pioneer, visionary, artist, filmmaker, workaholic, obsessive, tough – but no amount of bite-sized nouns or adjectives can accurately describe who a person really was. Human beings are complex, but the towering reputation of one of 20th century’s most prominent figures – who has himself willfully and oftentimes propagandistically appropriated that brand – makes it harder to believe that figures of American history were real individuals who rose, ate, bathed, and worked.

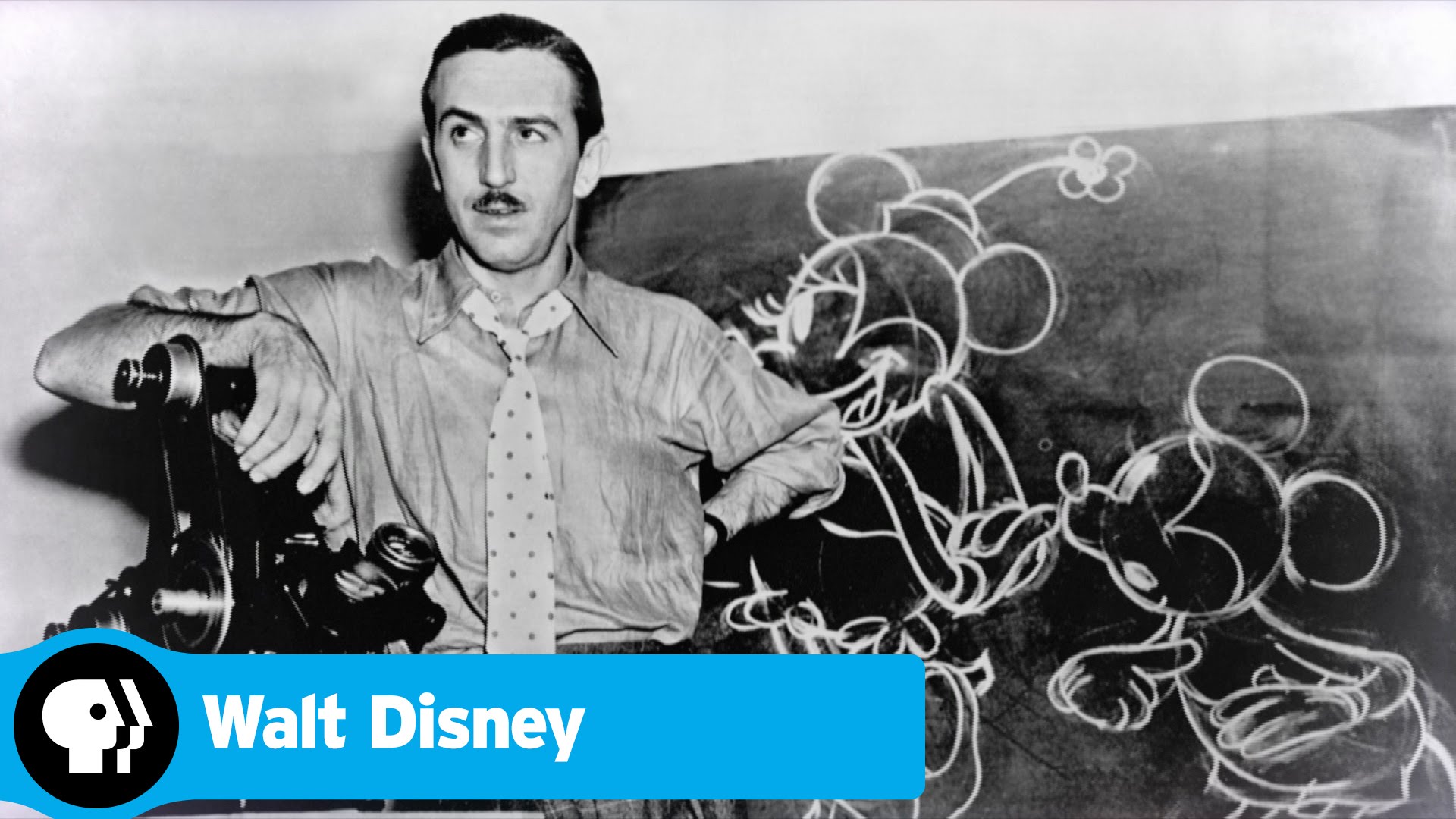

PBS’s two-part four-hour documentary on Walt Disney – which aired under the extensively researched American Experience program – sought to create the archetype of Disney biographies, with all other Disney documentaries (“Walt: The Man Behind the Myth”, “Walt & El Grupo”, “The Hand Behind the Mouse”, etc.) as supplementary material. It goes down the line, acting like a standard biography, from the childhood of the individual to the death of the icon, and takes time to strategically analyze pivotal points in Disney’s life, and the psyche behind his decisions. The enthusiastic Disney fans would recognize the few Disney Legends that litter the screen, who repeat the same stories they have been telling for years, and who have added a legitimacy and connective tissue to Walt Disney’s era. After all, they personally knew and spoke to Walt Disney. However, several historians and biographers, most notably “Walt Disney: Triumph of the American Imagination” author Neal Gabler, shed new insights on the figure based on historical context and psychology.

PBS’s two-part four-hour documentary on Walt Disney – which aired under the extensively researched American Experience program – sought to create the archetype of Disney biographies, with all other Disney documentaries (“Walt: The Man Behind the Myth”, “Walt & El Grupo”, “The Hand Behind the Mouse”, etc.) as supplementary material. It goes down the line, acting like a standard biography, from the childhood of the individual to the death of the icon, and takes time to strategically analyze pivotal points in Disney’s life, and the psyche behind his decisions. The enthusiastic Disney fans would recognize the few Disney Legends that litter the screen, who repeat the same stories they have been telling for years, and who have added a legitimacy and connective tissue to Walt Disney’s era. After all, they personally knew and spoke to Walt Disney. However, several historians and biographers, most notably “Walt Disney: Triumph of the American Imagination” author Neal Gabler, shed new insights on the figure based on historical context and psychology.

There may be some who decry the armchair psychology of the historians and biographers, and it may seem they assume a bounty of unmitigated and subconscious thoughts of Disney’s, like his vehement hatred of his father’s strict upbringing tactics or his fanatical obsession with model railroads stemming from a disillusionment of the Walt Disney Studios post-studio strike. A standard historical recollection of Walt Disney’s life would not have worked as effectively if we did not deduce various aspects of his personality based on the appropriate decisions and actions.

Last year, I read a critical biography of Charlie Chaplin called “Chaplin: A Life”, written by psychologist Stephen Weissman, M.D. Much to the horror of the Chaplin family, especially Chaplin’s own actress daughter Geraldine Chaplin, the book accused Chaplin’s mother of being a syphilic tragedy, and his frequent characterizations of dirt-poor grovelers a repressed recreation of his own hated

Last year, I read a critical biography of Charlie Chaplin called “Chaplin: A Life”, written by psychologist Stephen Weissman, M.D. Much to the horror of the Chaplin family, especially Chaplin’s own actress daughter Geraldine Chaplin, the book accused Chaplin’s mother of being a syphilic tragedy, and his frequent characterizations of dirt-poor grovelers a repressed recreation of his own hated

alcoholic father. Before its publication, Geraldine Chaplin denounced the biography as slander, as many in the Disney community have done of Gabler’s biography of Disney. However, something can be said about the evidence-heavy and careful psychoanalysis of complex individuals like Chaplin and Disney. By utilizing research-based historians and biographers, most of who have not met Walt Disney personally and have critical, unbiased perspectives on the figure, there is a sort of contextualization and analytical insight into the transformation of a man into a myth. PBS maintains a good balance of the Disney historians and artists, men like Don Hahn and Floyd Norman, and professional film historians, like the intelligent and reliable Richard Schickel, who arguably knows more about classic Hollywood than any other literary film historian.

Chapter-based and hitting the standard notes (though oftentimes tonally inconsistent), the average Disney fan would not discover anything they had not already known about Walt Disney from a historical standpoint, but the level of mental depth that the special attempts to dig deep into – without upsetting the Walt Disney Company – comes close to the insights of the two-part “Sinatra” HBO documentary directed by Alex Gibney, though with less social context surrounding Walt Disney. Frank Sinatra was a man who sought to immerse himself in the social and political landscape of the 20th century – Walt Disney was a man who attempted (to the best of his abilities, despite his conservative views) to remove himself from those very same societies. Unlike, say, American Experience’s previous special on the life of Johnny Carson, the special fails to venture too deeply into the personality and the justifications of Walt Disney, owing perhaps to his juxtapositional personalities: that of a fantastical inspirer, and that of a ruthless driver.

Interesting footnotes and use of rare archival footage unearthed for the first time have an interesting effect on the perception of Walt Disney, and hearing actual concrete recordings of Walt talking to his mother and father on their 50th anniversary shows us, most likely, for the first time a casual and natural conversation with Walt Disney, away from the press interviews and the pre-recorded Disneyland segments. Part 1 of the documentary closes on the Screen Cartoonists Guild strike of 1941 and ends in a surprising archival recording of Walt Disney addressing his employees, explaining his reasons for the privilege of men in the workplace and revealing the startling casual sexism that permeated his era.

Because there is a public image that the Walt Disney Company has sought to maintain through the products they choose to acknowledge, the documentary addresses little social criticism of Walt. Over the years, rumors and allegations have persisted of Walt Disney’s worldview towards people of color and different ethnicities, with many figures accusing him of racism, anti-Semitism, or sexism. In various promotions, the producers of American Experience have stated they found no such evidence to support these allegations, and they chose to leave it out. A better, more conclusive solution, however, would’ve been to finally use the opportunity to set the record straight and deny the allegations once and for all. By refusing to face any fingers of political correctness, PBS and the Walt Disney Company have missed the best window of opportunity to absolve the legacy of the individual.

In Part 2, a large segment of the documentary is focused on the cultural impact of Disneyland, and goes through the creation of it so thoroughly that there’s an obvious reverence for the theme park and its place in the world. The special explains of its popularity: “It was the CliffNotes version of American history and culture.” Disneyland was an easy representation of the affection and enthusiasm of America, and its genuine sincerity – despite its artificiality and idealization – was something that the world desperately longed for, and would eventually greet with open arms. “Such perfection did not belong to models,” Surrealist artist Salvador Dali expressed to Disney after being given a tour of his model railroad. Disney’s ambitions became bigger, and he sought to impact the culture – he was obsessed with the small-town ideal, constantly rewriting his own life to fit that standard, and with Disneyland, he had the opportunity to rewrite the life of others into that nostalgic idealism.

In Part 2, a large segment of the documentary is focused on the cultural impact of Disneyland, and goes through the creation of it so thoroughly that there’s an obvious reverence for the theme park and its place in the world. The special explains of its popularity: “It was the CliffNotes version of American history and culture.” Disneyland was an easy representation of the affection and enthusiasm of America, and its genuine sincerity – despite its artificiality and idealization – was something that the world desperately longed for, and would eventually greet with open arms. “Such perfection did not belong to models,” Surrealist artist Salvador Dali expressed to Disney after being given a tour of his model railroad. Disney’s ambitions became bigger, and he sought to impact the culture – he was obsessed with the small-town ideal, constantly rewriting his own life to fit that standard, and with Disneyland, he had the opportunity to rewrite the life of others into that nostalgic idealism.

As the special approached the 1950s era of Disney’s life, there are valid mid-century cultural contexts that are provided to accurately describe Americana at the time – none more evident than the craze of Davy Crockett. Something I’ve always been curious about was: if Davy Crockett was so popular and beloved in the mid-century, why hasn’t the figure endured as much as Elvis Presley or The Beatles? There is something distinctly Americana about Davy Crockett, but it always seemed to be looked back at as a product of the 1950s. Why don’t we talk about the Disneyland opening telecast the way we talk about The Beatles on Ed Sullivan? And yet, there seems to be something about Disneyland television show itself that made it the epitome of ‘50s culture.

Perhaps it is due to the legacy of the Walt Disney Studios at its height during the 1950s, with Walt Disney’s public persona in the cultural mindset, the arrival of a revolutionary theme park, a plethora of animated and live-action products gracing both the film and television markets, not to mention the marketing and merchandising of Disney products. It can be astutely observed that with the death of Walt Disney came the death of the Disney Studios as the mainstream, and slowly the cultural touchstone became a fading mid-century fad throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, until it was repurposed and revitalized as a massive multi-media corporation helmed by executives Michael Eisner and Frank Wells in the ‘90s, who for all intents and purposes, reappropriated the company as a business and an industry.

There is a perpetual theme of Walt Disney’s continuous carelessness and naivety towards the way the world works, citing the idealize d nostalgia of his Midwestern upbringing as a focal point of his life philosophy – all of which would eventually lead up to the creation of Disneyland. There is a sense that

d nostalgia of his Midwestern upbringing as a focal point of his life philosophy – all of which would eventually lead up to the creation of Disneyland. There is a sense that

Disney habitually regressed to his childhood and idealization of the small-town, and that insofar explains Disney’s confusion when it comes to intellectualized accusations of romanticism – such as the stereotypical “Song of the South”. Walt Disney’s nostalgia and romanticism for an America that didn’t exist – but should have existed – removed from his mind the social and cultural context that he was living in – such as the Civil Rights Movement – and he ventured on, despite the outcries of the intellectuals. “Don’t they understand? I like corn!” he expressed irritatingly to his son-in-law after a negative review of one of his live-action films.

In the end, Walt Disney knew his brand, and he knew that what he wanted to offer to the world was something that was better than reality, something that could not be contextualized by the times he lived in. He didn’t care about social messages or criticism, Walt Disney followed his heart and his instincts, using all the charm and enthusiasm that he held for the world to make something removed from the world. To Disney, it wasn’t just escapism, it was a different way of thinking – a better way of thinking.

And that’s what was so unique about Disney. He was an inspirer who glowed at the thought of the perfect American life that he could only ever express those themes in his products. Disney was so successful with audiences because he believed in the conviction of every last one of his films. He created a world crafted by his own ethics, aesthetics, and perspectives. He knew something about the American spirit that no one else did – that we craved the perfect idealization.

If you want to learn more about Walt Disney, visit the PBS website for exclusive videos, photos, and additional content.