When the Walt Disney Archives took on the task of creating an expansive, immersive exhibition to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of The Walt Disney Company, it looked for inspiration from Walt Disney himself. Rather than covering the company’s history in chronological order, the exhibition is organized in 10 galleries that reflect Walt’s guiding philosophies.

“It was a little over five years ago I started talking about the idea of this exhibition,” says Becky Cline, director of the Walt Disney Archives. “The idea was to use Walt’s philosophies to organize the exhibition—going back to the roots of the company and not doing a chronological retelling.” A major concern with recounting company history year by year was that younger guests, especially children, would not encounter the contemporary stories and characters they’re most familiar with until deep into the exhibition. Since the experience needed to delight guests of all ages from entry to exit, a traditional linear approach just wouldn’t have worked.

Cline notes that “it’s so much more compelling to use an emotional arc based on Walt Disney himself—to say, ‘This is what made Walt Disney such a visionary and a genius. These were his philosophies.’”

Thus did Disney100: The Exhibition—now open at The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with a second unit debuting April 18 in Munich, Germany—takes its shape from those ideas. It has galleries themed around powerful storytelling (“Where Do the Stories Come From?”), emotionally rich character development (“The Illusion of Life”), and technological innovations (“Innoventions”), to name a few. “These are the concepts that [Walt] used when he created the bedrock of this company,” Cline says, “and it’s what we’ve continued to do ever since. Storytelling is still paramount, as is personality in our animated characters. You have to have emotion. You’ve got to tug at the heartstrings of the audience.”

Anyone who has enjoyed the intricate soundscapes of The Mandalorian on Disney+ or watched fan videos inspired by “We Don’t Talk About Bruno,” from Encanto (2021), can attest to “The Magic of Sound and Music” in Disney storytelling, as another aptly titled exhibition gallery investigates. As the creator of the first animated film with synchronized sound and music (Steamboat Willie, 1928), Walt Disney knew that what audiences hear was as important as what they see. “He didn’t make music personally, but he was fascinated by it,” Cline says. Walt created his Silly Symphony series of music-focused animated shorts shortly after the introduction of Mickey Mouse, including such milestones as The Skeleton Dance (1929) and Flowers and Trees (1932), the first cartoon in Technicolor®. “There’s very little dialog in them. They’re driven by music, tied to the visuals,” Cline notes. The series also produced a “Bruno”-size popular-music hit in “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?,” from Three Little Pigs (1933).

Of course, songs were integral to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), and music was the driving force behind later Walt projects such as Fantasia (1940) and Make Mine Music (1946), which featured segments including “Peter and the Wolf.” “Walt knew his audience really, really well, and that included the music that they liked and the music that they appreciated,” Cline says. It’s a strength of Disney storytelling that continues to this day, on the cusp of the theatrical release of the reimagined live-action feature The Little Mermaid, encompassing both the Oscar®-winning music of the 1989 animated classic and three new songs from Disney Legend Alan Menken and Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Walt also understood that music was a universal language, Cline notes, a power reflected in the exhibition, where guests can listen to familiar Disney songs sung in languages from all around the world—one of the many interactive experiences designed exclusively for this exhibition.

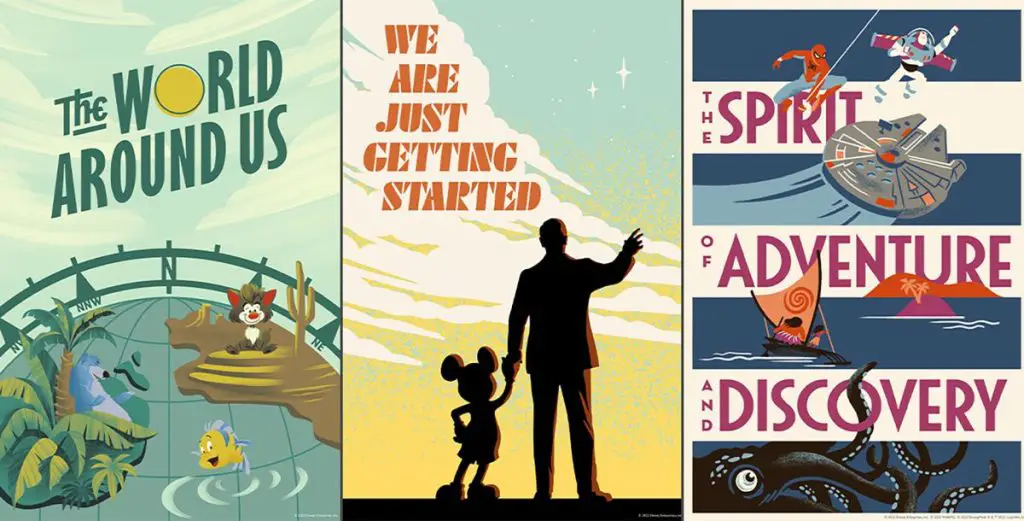

Some gallery titles speak for themselves, such as “The Spirit of Adventure and Discovery.” “Many of the first films that Walt made that were completely live-action were adventure stories,” Cline says, naming in particular Treasure Island (1950), The Sword and the Rose (1953), and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954). “He made comedies and historical stories as well, but he often leaned towards adventure and discovery.” Not surprisingly, Disney Legend George Lucas “has always said that he was inspired by the films of Walt Disney when he was a kid,” Cline adds. Naturally, the related gallery in Disney100: The Exhibition covers everything from those 1950s classics through the latest stories from the Star Wars universe and from Marvel, as well as 21st-century Disney live-action features such as the Pirates of the Caribbean movies and Jungle Cruise (2021).

As for the gallery titled “The World Around Us,” “Walt Disney was an early conservationist,” Cline says, and with his True-Life Adventures film series, starting in the late 1940s, “he basically invented the modern nature documentary.” The exhibition gallery honors those movies as well as their modern successors, the documentary films of Disneynature, while also pointing out the environmental messages vital to other Disney creations, such as Bambi (1942) and Disney’s Animal Kingdom Theme Park (which opened at Walt Disney World Resort on Earth Day in 1998).

The full cornucopia of Disney Parks across the globe is included in the gallery titled “Your Disney World: A Day in the Parks,” with particular attention on how today’s parks and attractions trace their origins to the original Disneyland Park, which opened in 1955 and thereby invented the theme park industry. This gallery, Cline says, offers guests a deep dive into many of the parks’ development, in part through one of the exhibition’s interactive experiences, while also celebrating Walt’s love of immersive storytelling.

Appropriately, Walt himself welcomes guests to Disney100: The Exhibition, delivering a short welcome in his own voice and seemingly in person, as a life-size image of Walt appears to speak on the Disney MagicStage, just before the entrance to the first gallery. His speech was assembled from two archival recordings; his visual presence was a collaboration among Disney StudioLAB, DisneyResearch|Studios, and Industrial Light & Magic, which utilized cutting-edge technology to bring Walt to life digitally—with the supervision of the Walt Disney Archives ensuring authenticity.

No doubt Walt himself would be proud of the response to the exhibition so far. “It’s been very positive,” Cline says. “We’ve received accolades from the press and gotten great response from visitors. I’ve been really touched by how much people love this. People are hearing about it through the grapevine or through social media, and I have friends calling me and telling me, ‘I’m going to go see it. I bought my tickets.’”